My white cloud gave out on the last four-day rotation. We had four cardiac arrest patients in two rotations, 8 days (and an apartment fire with a total of five patients, but I'll save that story for later). Surprisingly enough, we got return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) on all four, and three have survived past the 24-hour mark.

I was planning to write up three, and then we had the fourth, and the stories are just too long to tell. I'll try and summarize briefly.

* * *

Patient #1 was an unwitnessed arrest in a parking lot, very brady on arrival, v-fib soon after, transported immediately (work a code in a mud puddle in a parking lot? no thanks), tubed and everything enroute, shocked three times, the third shock at the hospital driveway ended up getting pulses back. He was very sick, however -- a primary respiratory arrest -- and died 20 hours later in ICU.

* * *

Patient #2 was a witnessed arrest at home, v-fib on arrival. Fire shocked him once, put in an EZ-IO, and had started CPR when we arrived. We worked him for 20 minutes onscene, going from fib to asystole to fib to v-tach to ugly sinus tach with pulses. He got lots of drugs, including early bicarb and amiodarone after pulses were back to try and get things working a bit better.

We did a 12-lead in the driveway -- massive STEMI. Code 3 to a cath lab hospital, transmitted the 12-lead. He started to have some spontaneous breaths, and then coughed the balloon of the tube out. Crap. We pulled over, got him reintubated.

He went up to the cath lab soon after we arrived, and after a successful cath went to the ICU, where at last report he remained in critical condition.

* * *

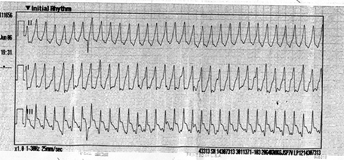

Patient #3 was a witnessed arrest in a bar on Christmas day. Complained of acid reflux and just plain dropped. Bystander CPR in progress. We start CPR, get him on the monitor. V-fib. Shock once. Converts. Get him tubed.

He has a perfusing rhythm and blood pressure almost immediately. Do a 12-lead right there on the bar floor. I should scan the strips, but the monitor reads "Inferior-posterior infarct" and "anterior infarct" on one shot, and then told us "septal infarct," "anterolateral injury pattern," and "inferior injury pattern" a few minutes later. I thought it just looked all bad.

Transmitted the strip -- I actually called the inital report from the bar, bagging with one hand. STEMI activation. We gave him an antiarrythmic -- I honestly can't remember if it was amio or lidocaine, I was on the airway -- and some versed because he was bucking the tube, and transported.

He coded again in the ED. Shocked 4 or 5 times. More drugs. Taken up to the cath lab. 100% occlusion of the LAD. Ballooned, stented. Called the ICU the next day. He'd been shocked twice more there, probably reperfusion ischemia. Then we had four days off.

Come back on New Year's Eve. Call the ICU. Not there. Dead, or to a floor, I wonder. To a floor would be cool. Call registration to check. Not in the hospital, they say.

Discharged, they say.

To home.

Unbelievable.

* * *

Patient #4 was after New Year's. Taking a cold shower. Family heard him drop. We found him in the bathtub. Agonal brady rhythm. CPR, IV, epi. What do you know, his heart kicked right back over and got going again. 12 lead was unremarkable. He tried to tank his pressure on the way in, but the fastest med control consult later by my lead paramedic and we had dopamine orders. That perked him right up.

The consensus among us was that the cold water stimulated his mammalian diving reflex, which caused him to brady down, which caused either a hypoxic bradycardic spiral, or a syncopal event which closed off his airway. Either way it wasn't a big cardiac event and I'm hopeful for his prognosis. Haven't heard anything yet, however.

* * *

So, statistically, having saved had 4 field ROSC patients in 2 weeks, I won't have any other saves for a long, long time. We'll see about that, though. I've got four shiny little Code Save pins coming, and some Starbucks cards for sending in tubes of blood for a Sudden Unexplained Death study.

Oh, and I've got a few other stories to write up, like the apartment fire and the patient who Should Not Have Refused.

At this rate, I'll get those out by February.

10 years ago